Countering Code Injection Attacks: A Unified Approach

Dimitris Mitropoulos

Vassilios Karakoidas

Panos Louridas

Diomidis Spinellis

Department of Management Science and Technology

Athens University of Economics and Business

{dimitro, bkarak, louridas, dds}@aueb.gr

Abstract

Code injection exploits a software vulnerability through which a

malicious user can make an application run unauthorized code.

Server applications frequently employ dynamic and domain-specific

languages, which are used as vectors for the attack.

We propose a generic approach that prevents the class

of injection attacks involving these vectors:

our scheme detects attacks by using location-specific signatures

to validate code statements. The signatures are unique identifiers

that represent specific characteristics of a statement's execution.

We have applied our approach successfully to defend against

attacks targeting SQL, XPath and JavaScript.

1 Introduction

Most software vulnerabilities derive from a relatively small number of

common programming errors that lead to security holes [

55,

37,

27,

50].

According to SANS (Security Leadership Essentials For

Managers)

1 two programming flaws

alone were responsible for more than 1.5 million security breaches

during 2008.

Although computer security is nowadays standard fare in academic curricula

around the globe, few courses emphasize secure

programming techniques [

47]. For instance, during a standard

introductory C course, students may not learn that using the

gets function could make code vulnerable to

an exploit [

43,

33]. The situation is similar in web programming.

Programmers are not aware of security loopholes inherent to the code

they write; in fact, knowing that they program using higher level

languages than those prone to security exploits, they may assume that these

render their application immune from exploits stemming from

coding errors.

One common trap into which programmers fall concerns user input,

assuming, for example, that only numeric characters will be entered

by the user, or that the input will never exceed a certain length.

Programmers may think, correctly, that a

high-level (usually scripting) language in a web application will

protect them against buffer overruns.

Programmers may also think, incorrectly, that input is not a security issue

any more. That is wrong. Their assumptions can lead to the processing

of invalid data that a malicious user can introduce into a program and

cause it to execute malicious code. This class of exploits are

known as

code injection attacks (CIAs). In this

article we present an approach that counters a specific class of

cias in a novel way.

2 Code Injection Attacks

Code injection is a technique to introduce code into a computer

program or system by taking advantage of unchecked assumptions the

system makes about its inputs. Code injection attacks are

one of the most damaging class of

attacks [

20,

46,

42,

38,

41] because:

- they can occur in different layers, like databases, native

code, applications, libraries and others; and

- they span a wide range of security and privacy issues, like

viewing sensitive information, destruction or modification of

sensitive data, or even stopping the execution of the entire

application.

Despite many countermeasures that have been proposed the number of

CIAs has been

increasing.

2

Malicious users seem to find new ways to introduce compromised

embedded executable code to applications by using a variety of

languages and techniques.

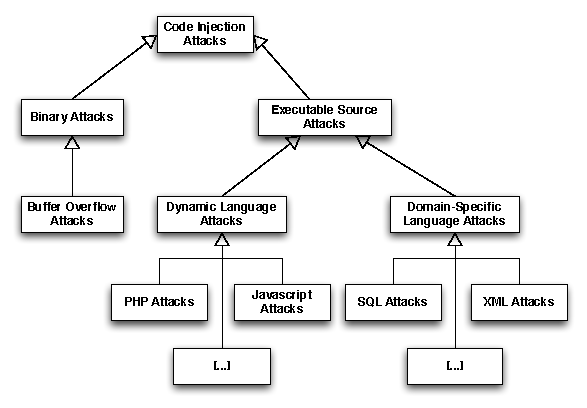

Figure

1 presents a taxonomy of CIAs, divided

in two basic categories. The first involves binary code and the second

executable source code.

Figure 1:

A taxonomy of code injection attacks

2.1 Binary Code Injection

Binary code injection involves the insertion of binary code in a

target application to alter its execution flow and execute inserted

compiled code. This category includes buffer-overflow

attacks [

19,

33], a staple of security problems. These attacks are

possible when the bounds of memory areas are not checked, and access

beyond these bounds is possible by the program. By taking advantage of

this, attackers can inject additional data overwriting the existing

data of adjacent memory. From there they can take control over a

program, crash it or, even take control of the entire host machine.

C and C++ are vulnerable to this kind of attacks since typical

implementations lack a protection scheme against overwriting data in

any part of the memory. Specifically, they do not check if the data

written to an array is within its boundaries. In comparison, Java

guards against such attacks by preventing access beyond array bounds,

throwing a runtime exception.

2.2 Source Code Injection

Code injection also includes the use of source code, either of

Domain-Specific Languages (DSLs) or

Dynamic Languages.

DSL injection attacks constitute an important subset of code

injection, as DSL languages like SQL and XML play an

important role in the development of web applications. For instance,

many applications have interfaces where a user enters input to

interact with the application's data, thereby interacting with the

underlying relational database management system (RDBMS). This

input can become part of a SQL statement and executed on the

target RDBMS.

A code injection attack that exploits the vulnerabilities of these

interfaces is called an "SQL injection attack" [

26,

8,

2].

One of the most common forms of such an exploit involves taking advantage of

incorrectly filtered quotation characters. For instance, in a login

page, besides the user name and password input fields, there is often

a separate field where users can input their e-mail address, in case

they forget their password. The statement that is executed can have

the following form:

SELECT password FROM users WHERE email = 'john@example.com';

If a sloppy programmer builds the SQL

statement on the fly by piecing together a template of the form:

SELECT password FROM users WHERE email = '<user_input>'

then an attacker could view every password in the table by using the

string

anything' OR 'x'='x as input. Savvy programmers could use

a language's libraries, like PHPs

mysql_real_escape_string() and detect malformed input; or they

could use prepared SQL statements, instead of statement

templates. Unfortunately, the number of SQL injection attacks

suggest that programmers are not always that careful.

Dynamic languages pose a related problem [

44,

16].

Python, Perl, JavaScript, and PHP are languages that have

the capability of interpreting themselves and execute code through

a method called

eval. A simple example of a dynamic

language-driven attack is an input string

that is fed into an

eval() function call, e.g., in

php:

3

$variable = $_GET['var'];

$input = $_GET['value'];

eval('$variable = ' . $input . ';');

The user may pass into the

value parameter code that will

execute in the server. If

value is

10 ; system("touch foo");

then a file will be created on the server; it is easy

to imagine more detrimental instances.

3 Tools and Current Approaches

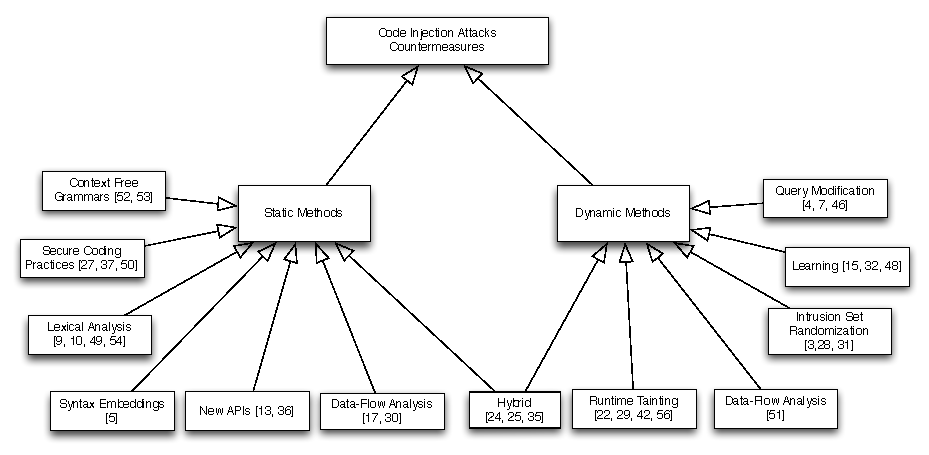

There are two basic approaches that detect injection vulnerabilities,

static and dynamic. A taxonomy of CIAs countermeasures appears in

Figure

2.

Figure 2:

A taxonomy of CIAs countermeasures

3.1 Static Methods

Static analysis involves the inspection of computer code

without actually executing the program.

The main idea behind static analysis is to identify software defects

during the development phase.

Currently, there are many modern software development processes

that use static checkers for security as their integral parts [

6,

21,

18].

The most straightforward and sensible approach is

the adoption of

secure coding practices [

27,

50,

37], like the

ones we mentioned above to prevent SQL code injection. However,

this does not always happen, as programmers may not be aware of them,

or time schedules may be tight, encouraging

sloppy practices instead.

Lexical analysis is a flexible method extensively

used to detect buffer overflow vulnerabilities.

To do so, a lexical analyzer recognizes character sequences

and transforms them into tokens.

Then, the resulting tokens are associated with vulnerable

function calls susceptible to buffer overflows like

gets,

strcpy and

scanf.

This approach is taken by security utilities

like ITS4,

4

Flawfinder

5 and

RATS

6

[

54,

10,

9,

49].

However, these tools suffer from several false positive and

negative reports [

11,

14].

Another static method that is tailored to localize injection

vulnerabilities is

data flow analysis.

Based on control-flow graph (CFG), data flow analysis can be applied to

connect unchecked user input with the execution of a code statement that is

based on this input and issue a notification about the vulnerability.

Pixy and Splint are data flow analysis tools used to detect code injection

vulnerabilities in web applications [

30,

17].

Data flow analysis exhibits less false positives and negatives than lexical

analysis but it suffers from a distinct runtime overhead [

1].

Wassermann and Su have proposed an approach that deals with

static analysis and coding practices [

52,

53].

Specifically, they automatically analyze the application's source code

to locate SQL statement invocations that are considered

unsafe. To analyze the code they utilize

context free grammars and language transducers [

39].

An approach to detect DSL-driven injection attacks involves

the introduction of

type-safe programming interfaces, like

DOM SQL [

36] and the Safe Query Objects [

13].

Both eliminate the incestuous relationship between untyped

Java strings and SQL statements, but don't address

legacy code, while also requiring programmers to learn

a radically new API.

Syntax embeddings have also been proposed to detect code that is

susceptible to various kinds of code injections [

5].

This approach embeds the grammar of a DSL language

into that of a host language and automatically reconstructs

code statements by adding functions that provide security layers.

Such an approach is quite interesting since it

introduces security features at a very early stage of software development.

Apart from the aforementioned methods, there are also some more practical

techniques introduced to prevent code injection attacks.

Livshits et al. [

34] protects browsers

from JavaScript injection by introducing specific modifications

to the browser's same-origin policy.

3.2 Dynamic Methods

Dynamic analysis can be seen as the next logical step of static analysis.

It inspects the behavior of a running system and does not

require access to the internals of the system.

On the dynamic front,

runtime tainting enforces security

policies by marking untrusted data and tracing its flow through the

program. For instance, the system by Haldar et al. [

56] covers

applications whose source code is written in Java, while the work

by Xu et al. [

22] covers applications whose source code

is written in C. A dynamic checking compiler

called WASC includes runtime tainting to prevent SQL and

script injection [

42]. To counter similar

attacks, SMask identifies tainted code by automatically

separating user input from legitimate code [

29].

This is done by introducing specific syntactic constructs

that handle server-side languages used for data management separately.

Such approaches generally require significant changes to

the compiler or the runtime system.

Instruction-set randomization (ISR) is another technique that

defends against most application-level binary code injection attacks.

This technique employs the notion of

encrypted software.

Kc et al. [

31] used ISR to counter different kinds

of injection. Their approach is based on the fact that a CIA

only succeeds if the injected code is compatible with the execution

environment that is created by using a randomization algorithm. The

attacker does not know the key to the algorithm and his injected code

will not succeed. Hu et al. [

28] proposed a software dynamic

translation-based implementation of ISR to fortify applications

against binary injection attacks. A similar approach was

also proposed by Barrantes et al. [

3].

Another dynamic approach that protects applications from SQL

attacks involves

query modification.

Here the modified statement is either reconstructed at runtime using

a cryptographic key that is inaccessible to the attacker [

4],

or the user input is tagged with delimiters that allow an augmented

SQL grammar to detect the attacks [

7,

46].

Both approaches require significant source code modifications though.

Dynamic data-flow analysis is also used to protect applications

from CIAs. SigFree is a tool that follows this approach

to block binary code injection attacks by detecting the presence

of malicious code [

51]. This is motivated by the fact that buffer overflow

attacks typically contain executables while legitimate client requests

never contain executables in most services.

Still, this is not always true and this is because the tool suffers

from false positives.

Finally, some approaches combine static analysis with runtime

monitoring. A general hybrid approach involves the identification of

SQL injection attacks using the program query language PQL [

35].

The PQL queries are evaluated through both a static analysis

and the dynamic monitoring of instrumented code.

AMNESIA, a tool that also detects SQL

injection attacks, associates a query model with the location of each

query in the application and then monitors the application to detect

when queries diverge from the expected model [

25,

24]. This idea is

related to

training approaches, based on the ideas of Denning's

original intrusion detection framework [

15]. Training

approaches record and store valid code statements and thereby detect

attacks as outliers from the set of valid statements.

An early approach called DIDAFIT recorded all database

transactions [

32]. Subsequent refinements tagged each

transaction with the corresponding application [

48].

In this paper, we propose a novel and generic approach of preventing

code injection attacks. Our approach can be seen as an improvement of

the training approach. To specify if an application is under attack we

use a blend of features that is unique for every vulnerable code

statement. The key property that differentiates our scheme is that

these features do not depend entirely on the code statement, but also

take into account elements from its execution context. At the end of

the training phase, a model of all legitimate statements is produced.

This entails almost zero false positive and false negative rates making our

approach robust and effective: at runtime, our scheme checks all code

statements for compliance with this model and can thus block the

statements that contain additional injected elements. Another distinct

advantage of our approach is that it can be easily retrofitted to any

system and it does not depend on the entity that is protected. We have

applied our scheme in three different cases with promising results.

4 Approach

Following our classification, we present an approach that

protects against two kinds of source code injection attacks: those that use an

application library to execute DSL code and those that exploit the

eval

function in dynamic languages.

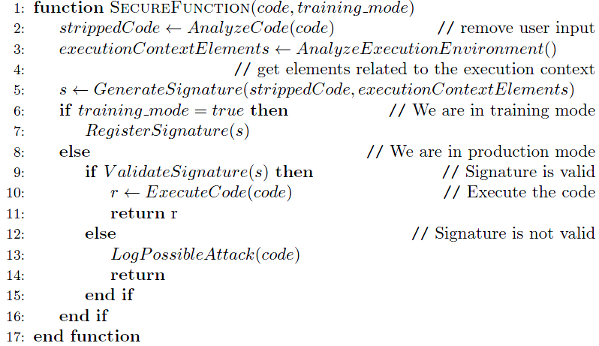

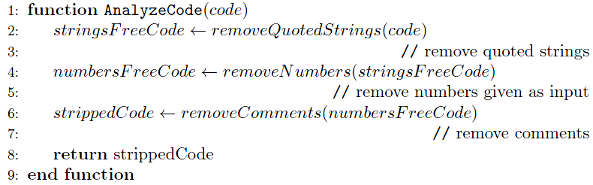

Figure

3 illustrates our proposed approach.

A

proxy application library accepts the request to execute

code from the application.

The code is examined and if it contains injected elements the library

issues an alarm.

Figure 3: Algorithm of the Proposed Approach

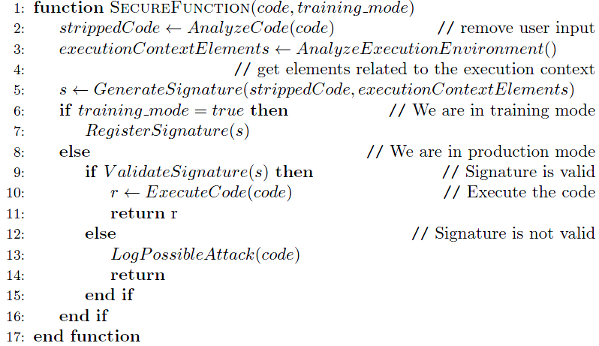

The proxy library operates in two modes, training and

production. During training, every vulnerable code statement is

associated with a location-specific signature. This signature is a

unique identifier that during production mode will determine if a CIA

is taking place. Before generating and storing a signature the proxy

library analyzes the code. Code analysis involves the complete removal of what

is expected as user input, i.e., string literals and numbers, so that

the signature is a template, and representative, of a class of user

inputs, omitting only the actual input received-in which

case it would be useless as a predictor. Then specific features related to the

execution context are

combined to create the signature identifier, which is registered as

valid in a auxiliary table where all known valid signatures are stored.

We describe these features in Section

5.

After the signature generation, the application's normal execution flow continues.

If the proxy application library is in production mode, the first two

steps are the same with the training mode. The code is analyzed in the

same manner and a signature is generated again. After the generation

of the signature, the library validates it by checking if it exists in

the table of valid signatures. If it does not, it means that an injection attack is

taking place. The library prevents the execution of the injected code

and specific details regarding the invalid call are logged.

5 Location-Specific Signatures

A key element of our approach is the efficient generation of

location-specific signatures. The legitimate signatures produced in

the training mode are based on features that when combined provide a

unique identifier. Some of these features depend entirely on the code

statement that is about to be executed. These include SQL

keywords in the case of an SQL statement, XML attributes

in the case of an XML code fragment, etc. Other features are

independent of the code statements, but depend on the execution flow

and environment: these include the caller method, its class name, the

connection between the application and the database, the line number

of the file that triggers an execution, and others.

The various features must be selected in such a way that every legitimate

vulnerable code statement at execution time is associated with one

signature in an injective relation; that is, every legitimate

vulnerable code statement is associated with at most one signature.

Literally, if

C is the set of all legitimate code statements of an application,

S is the set of the legitimate signatures

and

C and

S are disjoint sets, the following expression must stand:

|

f\colon J→ S is an injecton |

| (1) |

If it does, when a malicious user attempts an attack the injected code

will lead to a signature that does not exist in the table and the

attack will be intercepted. This requires the removal of actual user

input from the signature generating function. As presented in Figure

3,

this is done by the

AnalyzeCode function.

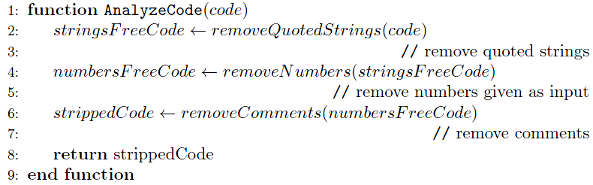

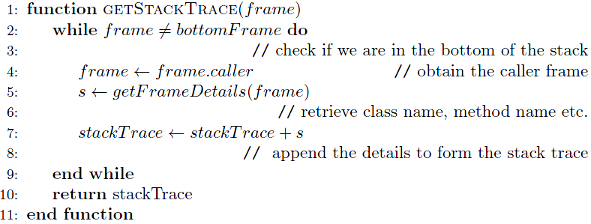

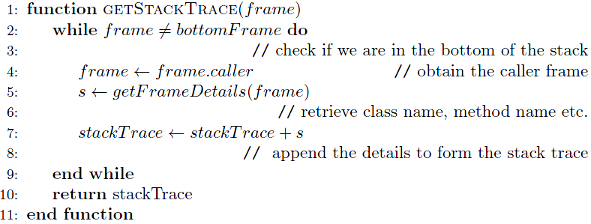

For this removal to take place the

AnalyzeCode function

follows the steps listed in Figure

4.

Figure 4: User Input Removal

Signature creation also requires the retrieval of the elements

that are related to the execution context. As illustrated in Figure

3 this is done by the

AnalyzeExecutionEnvironment

function. Depending on the attack, the elements extracted from this

function may vary. Hence it is implemented differently depending on

the type of the attack and the execution context. Based upon the

above, a valid signature is defined by the following, where + stands

for string concatenation:

|

S = AnalyzeCode(code) + AnalyzeExecutionEnvironment() |

| (2) |

To facilitate the handling of the signatures and ensure that they are

not manipulated in any way, a hash function is applied to the combined

elements before they are stored in the signature storage table.

6 Domain Specific Language Support

In earlier work, we demonstrated the validity of our approach for guarding

against injection attacks on DSLs. Specifically, we showed how it can guard

applications against two of the most common DSL-driven injection attacks,

namely SQL and XPath [

41,

40].

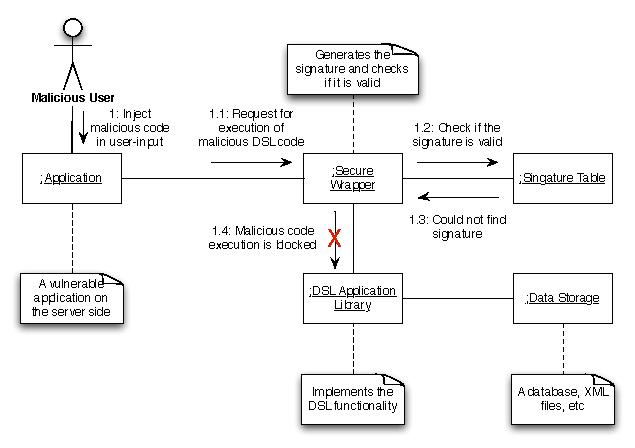

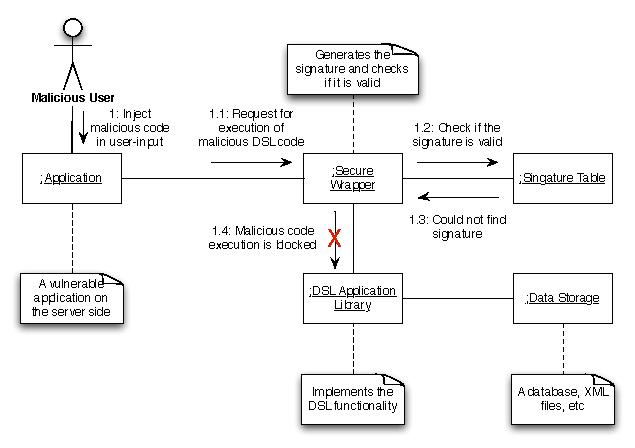

The general architecture behind both mechanisms is presented as a UML

communication diagram in Figure

5.

Figure 5: DSL-driven injection attack interception scenario

In the case of SQL, our mechanism, "SDriver/SQL",

is a JDBC (Java Database Connectivity)

driver

7

that adds the security properties of our approach against SQL injection.

It acts as a wrapper around other connectivity

drivers and it depends neither on the application nor on the RDBMS.

To protect applications against XPath injection we implemented

an XPath proxy library called SDriver/XPath.

The proxy library depends on the

java.xml.xpath2

package which provides an API for the evaluation of

xpath expressions and access to the evaluation environment. In

essence, SDriver/XPath wraps the default implementation of

XPath and adds our security features.

The library is application-independent, just like its SQL counterpart.

Both mechanisms can be easily used by existing programs: a programmer needs to

make only one change in the application's code to protect it.

In our implementations, the signatures created during the training mode involve

the stripped down statement (as presented in Figure

4) and a

critical element of the execution context of the application, the method

invocation stack trace. The stack trace is retrieved following Figure

6 (which is practically the implementation of the

AnalyzeExecutionEnvironment function in the DSL context) and it includes

the details of all methods and call location, from the method where a code

statement is executed down to the target method of the connectivity driver or the

XPath package.

The stack trace is essential for the signature in order to differentiate between

valid and invalid calls. For example, consider an application that will send the

password for a forgetful user via email by executing:

SELECT password from userdata WHERE id = 'Alice'

This same application could allow users to lock their terminal,

but allow the unlocking either with the user's password or with

the administrator password (the 4.3 BSD

lock command

behaved in this way). The corresponding query to verify the password on

the locked workstation would be as follows.

SELECT password from userdata WHERE id = 'Alice' OR id = 'admin'

It is now easy to see that a malicious user could obtain the

administrator's password by email by entering on the password retrieval form

the string

anything' OR 'x'='x as his user identifier.

Without the the differentiating factor of a stack trace, the preceding

query would have the same signature as the one used for unlocking the terminal,

and would escape a traditional signature-based protection system.

Figure 6: Traversing The Call Stack

We have evaluated our tools in terms of

detection accuracy

and

operation cost. For the accuracy testing we used simple

synthetic benchmarks,

8

notoriously vulnerable applications,

9 and a bundle of

previously evaluated real-world applications

10 [

23,

46]. We attempted a wide variety of attacks based on incorrectly

filtered quotation characters, incorrectly passed parameters, untyped

parameters, tautologies, and others [

2,

26]. Our mechanisms

successfully prevented all the attacks without suffering from false

positives or negatives.

To calculate the operation cost of SDriver/SQL, we measured

the overhead by executing a complex SQL statement, with and

without the mechanism. The

operation cost measures the cost

of the query execution inside the Java Virtual Machine, and not the

cost of the execution in the database. During production mode it is

below 35%; as the actual query execution time comprises the time

spent in the database (and the transfer to and from it), the effective

overhead to the user will be lower, depending on the complexity of the

query.

The SDriver/XPath library was tested for

operation cost against the

standard XPath library shipped with the Java Development Kit

(JDK). To use the XPath library one must compile

the XPath expression and then run it on the XML data. The

results are returned as a list of XML nodes. Our approach adds

the extra overhead only to the compilation phase, which is usually

executed only once, if the developer follows good coding practices.

The benchmark results showed that the library performed

in average 93% slower in the compilation phase than the standard

XPath library; similarly with SQL injection protection,

depending on the complexity of the query and how compilation fares

against execution, the relative delay experienced by the user will be

less.

Our scheme can be applied to all DSLs that are

integrated into GPLs using the pattern

Implementation:Embedding

as proposed by Mernik et al [

38].

This is because this pattern includes all DSLs that are using an

application library as their implementation scheme.

A drawback of our approach in both mechanisms is the need for

retraining after a new release.

If the application's code is altered, the new source code structure

invalidates existing query signatures. This is because stack elements

contain information about a method invocation including the method

name, the package, the file, and the line number. This necessitates a

new training phase.

7 Dynamic Language Support

To demonstrate that our scheme is applicable in the dynamic

language-driven injection context we experimented with the JavaScript

engine of Firefox in order to protect users from JavaScript injection

attacks. Although we are still protecting against code injection

attacks, we are now guarding the user's web browser and not a

server-side application as was the case in the previous two examples.

JavaScript is executed as a browser component, usually resulting on

compromising its resources for malevolent purposes. With a JavaScript

injection attack, a malicious user can follow the recent browsing

history of an unsuspecting user, steal tracking cookies and modify the

browsers behavior. JavaScript injection is considered a critical issue

in web application security mainly because it is associated with major

vulnerabilities like

cross-site scripting (XSS)

[

12,

57].

A large number of CIAs in JavaScript exploit the

eval

function [

16,

45,

57]. Such attacks

take advantage of the fact that

eval executes the code

passed to it in the same execution environment as the function's caller.

Attackers can also utilize

eval to put together strings and

form a pattern that the protecting mechanisms

of a web page consider dangerous and would normally strip out [

58,

45].

As a result, if a malicious user caches this function in a hidden script

of a web page, she can essentially manipulate the browser as she chooses.

A known way to do this, is by taking advantage the poor CSS

rendering of various browsers.

11

For example, with the following code fragment hidden in the

CSS of a web page:

<div id=mycode style="background:url('java

script:eval(document.all.mycode.expr)')"

expr="alert(document.cookie)"></div>

an attacker will maneuver the user's browser to execute the code

contained in the

expr variable.

Such an attack was used in the MySpace Samy XSS attack,

which utilized

eval to bypass the security measures taken by the

community creators and automatically add the attacker to the victim's friends,

while altering the victim's profile to add a copy of the attack code.

Firefox uses a JavaScript engine called

SpiderMonkey.

12

We modified the engine to prevent attacks that exploit the

eval function. To do so, when the

eval function is called

we obtain the complete path of the file that called the

eval

function (with the website's URL included) and the JavaScript

stack trace. By combining the two features we can generate a robust

signature that can detect attacks that include the

eval function

in their injected code. Since there are no elements from the

eval feed included in the signature for this case study code

analysis is not needed. Hence a signature can be defined by the

following:

|

S = AnalyzeExecutionEnvironment() |

| (3) |

The implementation of the stack traversal follows the same steps

shown in Figure

6.

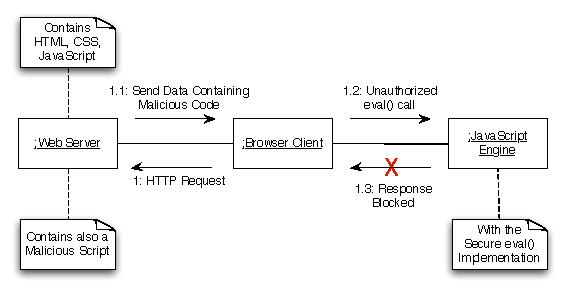

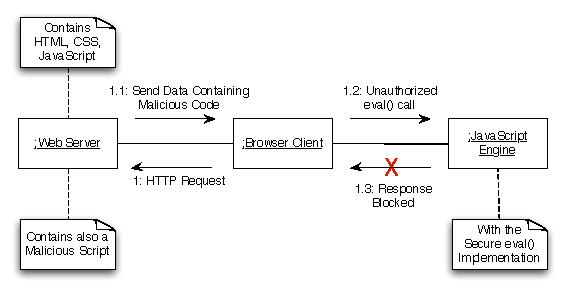

Figure 7: JavaScript injection attack interception scenario

Figure

7 illustrates a typical JavaScript

injection attack scenario as a UML communication diagram. The

scenario includes a web browser making an HTTP

request to a manipulated web page that contains a well-hidden script.

After the request, the page is downloaded in the user's browser and

the script is loaded and executed by the JavaScript engine. If the

malicious code contains the

eval function the attack is

intercepted because the method will be called from an

unrecorded file or with a different stack trace.

To evaluate our prototype in terms of

operation cost we added

timers and measured the execution time of our added functionality.

Since the feed of the

eval function is not included in a

legitimate signature and hence it does not affect our prototype, for a

fixed script fed to the

eval function, we measured the execution

time for different stack depths, from a direct call to

eval up

to a stack depth of 20. As a result we had twenty one measurements for

twenty one stack depths. The execution time is linear to the

JavaScript stack (

t = 17.68 + 4

d,

p << 0.05,

r2 = 0.9939, where

d is the stack depth).

To check the accuracy of our module we consulted

xssed.com

13 to find vulnerable, real-world

web pages and attack them by utilizing

eval. We performed tests on 3 top

ranking sites namely:

cnn.com14,

dhl.com15 and

reuters.com16. In all cases our

mechanism prevented the attack without encountering any false positives or

negatives.

An advantage of the scheme compared to the one proposed for the

dsl context is the fact that the need for retraining is not so

frequent, as it is only required after a change in the code that

alters the method call sequence. The training itself is not carried

out by the user since the user cannot be sure that during the training

the browser is executing legitimate code. A possible way to avoid this

is to create the signatures server-side and pass them on the user-side

during the users' first site visit via HTTPS.

8 Conclusions and Future Work

Unless an application is severely flawed, its vulnerabilities are

likely to be located in a few places, and attackers wishing to exploit

them are likely to try to "play around the rules". Such

opportunities are rare, and their exploitation entails forcing an

application to do something outside the normal course of events.

Exactly because such abnormal behavior stands out from the

application's normal conduct, it is possible to detect it and take

protective action when it occurs.

Our application takes advantage of this in order to prevent a broad

class of injection attacks. To distinguish between normal and abnormal

events, we identify and register vulnerable code statements using

unique signatures that we generate during a training phase. Then, at

runtime, our framework checks all statements for compliance with the

trained model and can thus block code statements containing additional

maliciously injected elements. The training phase can take place

during regression and user acceptance testing prior to release, so that

developers do not need to alter their working processes significantly.

The approach introduces a runtime overhead, but the overhead compares

favorably when related to the full execution cost of the protected

statements; with complex statements, it will be negligible.

The applicability of our approach to any GPL with

eval

capabilities hints at a possible generalisation to any GPL that

is able to execute its own programs. For instance, there is no

distinction between program and data in Lisp and its dialects.

Although we are not aware of attacks on these languages, their

variants are increasing in popularity.

A disadvantage of our scheme is that when a signature feature is

altered, a new training phase is necessary.

However, with the increased adoption of test-driven development,

and use of automated testing frameworks like JUnit, this

training phase can be easily repeated.

Despite warnings and advice for many years now, insecure software is

still released. One reason is that developers are wary of

incorporating into their practice cumbersome methods and unyielding

tools. Countering that, our approach is easy to use, requiring minimal

changes in existing code. Moreover, it can be extended to more domains

and languages than the three shown here.

The implementations of our libraries are available at

http://istlab.dmst.aueb.

gr/~dimitro/ssuite/.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Chuan Yue and Haining Wang for sharing with us details of

their SpiderMonkey instrumentation efforts. We would also like to thank

Konstantinos Stroggylos, Georgios Gousios and Titika Konstantinopoulou for their

insightful comments during the writing of this paper.

This research has been co-financed by the European Union (European Social Fund

- ESF) and Greek national funds through the Operational Program Ëducation and

Lifelong Learning" of the National Strategic Reference Framework (NSRF) -

Research Funding Program: Heracleitus II. Investing in knowledge society through

the European Social Fund.

References

- [1]

-

Ashish Aggarwal and Pankaj Jalote.

Integrating static and dynamic analysis for detecting

vulnerabilities.

In COMPSAC '06: Proceedings of the 30th Annual International

Computer Software and Applications Conference (COMPSAC'06), pages 343-350,

Washington, DC, USA, 2006. IEEE Computer Society.

- [2]

-

C. Anley.

Advanced SQL Injection in SQL Server Applications.

Next Generation Security Software Ltd., 2002.

- [3]

-

E. Barrantes, D. Ackley, S. Forrest, T. Palmer, D. Stefanovic, and D. Zovi.

Randomized instruction set emulation to disrupt binary code injection

attacks.

In CCS 2003: Proceedings of the 10th ACM Conference on Computer

and Communications Security, pages 281-289, October 2003.

- [4]

-

S. Boyd and A. Keromytis.

SQLrand: Preventing SQL injection attacks.

In M. Jakobsson, M. Yung, and J. Zhou, editors, Proceedings of

the 2nd Applied Cryptography and Network Security (ACNS) Conference, pages

292-304. Springer-Verlag, 2004.

Lecture Notes in Computer Science Volume 3089.

- [5]

-

Martin Bravenboer, Eelco Dolstra, and Eelco Visser.

Preventing injection attacks with syntax embeddings.

In GPCE '07: Proceedings of the 6th international conference on

Generative programming and component engineering, pages 3-12, New York, NY,

USA, 2007. ACM.

- [6]

-

Mason Brown and Alan Paller.

Secure software development: Why the development world awoke to the

challenge.

Inf. Secur. Tech. Rep., 13(1):40-43, 2008.

- [7]

-

G. Buehrer, B.W. Weide, and P.A. Sivilotti.

Using parse tree validation to prevent SQL injection attacks.

In Proceedings of the 5th international Workshop on Software

Engineering and Middleware, pages 106�-113. ACM Press, September 2005.

- [8]

-

CERT.

CERT vulnerability note VU282403.

Online http://www.kb.cert.org/vuls/id/282403, 2002.

Accessed, January 7th, 2007.

- [9]

-

Karl Chen and David Wagner.

Large-scale analysis of format string vulnerabilities in debian

linux.

In PLAS '07: Proceedings of the 2007 workshop on Programming

languages and analysis for security, pages 75-84, New York, NY, USA, 2007.

ACM.

- [10]

-

Brian Chess and Gary McGraw.

Static analysis for security.

IEEE Security and Privacy, 2(6):76-79, 2004.

- [11]

-

Brian Chess and Jacob West.

Secure programming with static analysis.

Addison-Wesley Professional, 2007.

- [12]

-

Ravi Chugh, Jeffrey A. Meister, Ranjit Jhala, and Sorin Lerner.

Staged information flow for javascript.

In PLDI '09: Proceedings of the 2009 ACM SIGPLAN conference on

Programming language design and implementation, pages 50-62, New York, NY,

USA, 2009. ACM.

- [13]

-

W.R. Cook and S. Rai.

Safe query objects: statically typed objects as remotely executable

queries.

In ICSE 2005: 27th International Conference on Software

Engineering, pages 97-106, 2005.

- [14]

-

Crispin Cowan.

Software security for open-source systems.

IEEE Security and Privacy, 1(1):38-45, 2003.

- [15]

-

Dorothy Elizabeth Robling Denning.

An intrusion detection model.

IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, 13(2):222-232,

February 1987.

- [16]

-

Manuel Egele, Peter Wurzinger, Christopher Kruegel, and Engin Kirda.

Defending browsers against drive-by downloads: Mitigating

heap-spraying code injection attacks.

In DIMVA '09: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on

Detection of Intrusions and Malware, and Vulnerability Assessment, pages

88-106, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2009. Springer-Verlag.

- [17]

-

David Evans and David Larochelle.

Improving security using extensible lightweight static analysis.

IEEE Softw., 19(1):42-51, 2002.

- [18]

-

Michael Fagan.

Design and code inspections to reduce errors in program development.

pages 575-607, 2002.

- [19]

-

James C. Foster, Vitaly Osipov, and Nish Bhalla.

Buffer Overflow Attacks.

Syngress Publishing, 2005.

- [20]

-

Aurélien Francillon and Claude Castelluccia.

Code injection attacks on harvard-architecture devices.

In CCS '08: Proceedings of the 15th ACM conference on Computer

and communications security, pages 15-26, New York, NY, USA, 2008. ACM.

- [21]

-

Johan Gregoire, Koen Buyens, Bart De Win, Riccardo Scandariato, and Wouter

Joosen.

On the secure software development process: Clasp and sdl compared.

In SESS '07: Proceedings of the Third International Workshop on

Software Engineering for Secure Systems, page 1, Washington, DC, USA, 2007.

IEEE Computer Society.

- [22]

-

Vivek Haldar, Deepak Chandra, and Michael Franz.

Dynamic taint propagation for Java.

In ACSAC '05: Proceedings of the 21st Annual Computer Security

Applications Conference, pages 303-311, Washington, DC, USA, 2005. IEEE

Computer Society.

- [23]

-

W. G. Halfond and A. Orso.

AMNESIA: analysis and monitoring for neutralizing SQL-injection

attacks.

In Proceedings of the 20th IEEE/ACM international Conference on

Automated Software Engineering, pages 174�-183. ACM Press, November 2005.

- [24]

-

W. G. Halfond and A. Orso.

Preventing SQL injection attacks using AMNESIA.

In ICSE 2006: Proceedings of the 28th International Conference

on Software Engineering, pages 795�-798. ACM Press, May 2006.

- [25]

-

William G. J. Halfond and Alessandro Orso.

Combining static analysis and runtime monitoring to counter

SQL-injection attacks.

In WODA '05: Proceedings of the Third International Workshop on

Dynamic Analysis, pages 1-7, New York, NY, USA, 2005. ACM Press.

- [26]

-

William G.J. Halfond, Jeremy Viegas, and Alessandro Orso.

A classification of SQL-injection attacks and countermeasures.

In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Secure Software

Engineering, March 2006.

- [27]

-

Michael Howard and David LeBlanc.

Writing Secure Code.

Microsoft Press, Redmond, WA, second edition, 2003.

- [28]

-

Wei Hu, Jason Hiser, Dan Williams, Adrian Filipi, Jack W. Davidson, David

Evans, John C. Knight, Anh Nguyen-Tuong, and Jonathan Rowanhill.

Secure and practical defense against code-injection attacks using

software dynamic translation.

In VEE '06: Proceedings of the 2nd international conference on

Virtual execution environments, pages 2-12, New York, NY, USA, 2006. ACM.

- [29]

-

Martin Johns and Christian Beyerlein.

Smask: preventing injection attacks in web applications by

approximating automatic data/code separation.

In SAC '07: Proceedings of the 2007 ACM symposium on Applied

computing, pages 284-291, New York, NY, USA, 2007. ACM.

- [30]

-

Nenad Jovanovic, Christopher Kruegel, and Engin Kirda.

Pixy: A static analysis tool for detecting web application

vulnerabilities (short paper).

In SP '06: Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE Symposium on Security

and Privacy, pages 258-263, Washington, DC, USA, 2006. IEEE Computer

Society.

- [31]

-

Gaurav S. Kc, Angelos D. Keromytis, and Vassilis Prevelakis.

Countering code-injection attacks with instruction-set randomization.

In CCS '03: Proceedings of the 10th ACM conference on Computer

and communications security, pages 272-280, New York, NY, USA, 2003. ACM.

- [32]

-

Sin Yeung Lee, Wai Lup Low, and Pei Yuen Wong.

Learning fingerprints for a database intrusion detection system.

In Dieter Gollmann, Günter Karjoth, and Michael Waidner, editors,

ESORICS '02: Proceedings of the 7th European Symposium on Research in

Computer Security, pages 264-280, London, UK, 2002. Springer-Verlag.

Lecture Notes In Computer Science 2502.

- [33]

-

Kyung-Suk Lhee and Steve J. Chapin.

Buffer overflow and format string overflow vulnerabilities.

Software: Practice and Experience, 33(5):423-460, 2003.

- [34]

-

Benjamin Livshits and Úlfar Erlingsson.

Using web application construction frameworks to protect against code

injection attacks.

In PLAS '07: Proceedings of the 2007 workshop on Programming

languages and analysis for security, pages 95-104, New York, NY, USA, 2007.

ACM.

- [35]

-

Michael Martin, Benjamin Livshits, and Monica S. Lam.

Finding application errors and security flaws using PQL: a program

query language.

In OOPSLA '05: Proceedings of the 20th Annual ACM SIGPLAN

Conference on Object Oriented Programming, Systems, Languages, and

Applications, pages 365-383, New York, NY, USA, 2005. ACM Press.

- [36]

-

Russell A. McClure and Ingolf H. Krüger.

SQL DOM: Compile time checking of dynamic SQL statements.

In ICSE '05: Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on

Software Engineering, pages 88-96, 2005.

- [37]

-

Gary McGraw.

Software Security: Building Security In.

Addison-Wesley Professional, 2006.

- [38]

-

Marjan Mernik, Jan Heering, and Anthony M. Sloane.

When and how to develop domain-specific languages.

ACM Computing Surveys, 37(4):316-344, 2005.

- [39]

-

Yasuhiko Minamide.

Static approximation of dynamically generated web pages.

In WWW '05: Proceedings of the 14th international conference on

World Wide Web, pages 432-441, New York, NY, USA, 2005. ACM.

- [40]

-

Dimitris Mitropoulos, Vassilios Karakoidas, and Diomidis Spinellis.

Fortifying applications against XPath injection attacks.

In A. Poulymenakou, N. Pouloudi, and K. Pramatari, editors, MCIS

2009: 4th Mediterranean Conference on Information Systems, pages

1169-1179, September 2009.

- [41]

-

Dimitris Mitropoulos and Diomidis Spinellis.

SDriver: Location-specific signatures prevent SQL injection

attacks.

Computers and Security, 28:121-129, May/June 2009.

- [42]

-

Susanta Nanda, Lap-Chung Lam, and Tzi-cker Chiueh.

Dynamic multi-process information flow tracking for web application

security.

In MC '07: Proceedings of the 2007 ACM/IFIP/USENIX international

conference on Middleware companion, pages 1-20, New York, NY, USA, 2007.

ACM.

- [43]

-

Robert Seacord.

Secure coding in C and C++: Of strings and integers.

IEEE Security and Privacy, 4(1):74, 2006.

- [44]

-

Nuno Seixas, José Fonseca, Marco Vieira, and Henrique Madeira.

Looking at web security vulnerabilities from the programming language

perspective: A field study.

In ISSRE '09: Proceedings of the 2009 20th International

Symposium on Software Reliability Engineering, pages 129-135, Washington,

DC, USA, 2009. IEEE Computer Society.

- [45]

-

H. Shahriar and M. Zulkernine.

Mutec: Mutation-based testing of cross site scripting.

In IWSESS '09: Proceedings of the 2009 ICSE Workshop on Software

Engineering for Secure Systems, pages 47-53, Washington, DC, USA, 2009.

IEEE Computer Society.

- [46]

-

Zhendong Su and Gary Wassermann.

The essence of command injection attacks in web applications.

In Conference Record of the 33rd ACM SIGPLAN-SIGACT Symposium on

Principles of Programming Languages POPL '06, pages 372�-382. ACM Press,

January 2006.

- [47]

-

Marianthi Theoharidou and Dimitris Gritzalis.

Common body of knowledge for information security.

IEEE Security & Privacy, 5(2):64-67, 2007.

- [48]

-

Fredrik Valeur, Darren Mutz, and Giovanni Vigna.

A learning-based approach to the detection of SQL attacks.

In Klaus Julisch and Christopher Kruegel, editors, Intrusion and

Malware Detection and Vulnerability Assessment: Second International

Conference, DIMVA 2005, pages 123-140, July 2005.

Lecture Notes in Computer Science 3548.

- [49]

-

John Viega, J. T. Bloch, Tadayoshi Kohno, and Gary McGraw.

Token-based scanning of source code for security problems.

ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. Secur., 5(3):238-261, 2002.

- [50]

-

John Viega and Gary McGraw.

Building Secure Software: How to Avoid Security Problems the

Right Way.

Addison-Wesley, Boston, MA, 2001.

- [51]

-

Xinran Wang, Chi-Chun Pan, Peng Liu, and Sencun Zhu.

Sigfree: A signature-free buffer overflow attack blocker.

IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput., 7(1):65-79, 2010.

- [52]

-

Gary Wassermann and Zhendong Su.

An analysis framework for security in web applications.

In SAVCBS 2004: Proceedings of the FSE Workshop on Specification

and Verification of Component-Based Systems, pages 70-78, 2004.

- [53]

-

Gary Wassermann and Zhendong Su.

Sound and precise analysis of web applications for injection

vulnerabilities.

In PLDI '07: Proceedings of the 2007 ACM SIGPLAN conference on

Programming language design and implementation, pages 32-41, New York, NY,

USA, 2007. ACM Press.

- [54]

-

John Wil and Marjam Kamkar.

A comparison of publicly available tools for static intrusion

prevention.

In In Proceedings of the 7th Nordic Workshop of Secure IT

Systems, 2002.

- [55]

-

Glenn Wurster and P. C. van Oorschot.

The developer is the enemy.

In NSPW '08: Proceedings of the 2008 workshop on New security

paradigms, pages 89-97, New York, NY, USA, 2008. ACM.

- [56]

-

Wei Xu, Sandeep Bhatkar, and R. Sekar.

Taint-enhanced policy enforcement: A practical approach to defeat a

wide range of attacks.

In Security '06: Proceedings of the 15th USENIX Security

Symposium, pages 121-136, Berkeley, CA, August 2006. USENIX Association.

- [57]

-

Dachuan Yu, Ajay Chander, Nayeem Islam, and Igor Serikov.

Javascript instrumentation for browser security.

In POPL '07: Proceedings of the 34th annual ACM SIGPLAN-SIGACT

Symposium on Principles of programming languages, pages 237-249, New York,

NY, USA, 2007. ACM.

- [58]

-

Chuan Yue and Haining Wang.

Characterizing insecure javascript practices on the web.

In WWW '09: Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on

World wide web, pages 961-970, New York, NY, USA, 2009. ACM.

Footnotes:

1http://www.sans.org/

2http://www.sans.org/top-cyber-security-risks/,

http://cwe.mitre.org/top25/,

http://www.owasp.org/index.php/Category:OWASP_Top_Ten_Project

3http://seclists.org/lists/fulldisclosure/2006/May/0035.html

4http://www.cigital.com/its4/

5http://www.dwheeler.com/flawfinder/

6http://www.fortify.com/security-resources/rats.jsp

7http://java.sun.com/products/jdbc/driverdesc.html

8Our testing was based on standard

scenarios as described in

http://cwe.mitre.org/data/definitions/643.html

and

http://projects.webappsec.org/XPath-Injection.

9Daffodil can be obtained

from

http://www.daffodildb.com/crm/

10The applications

can be obtained from

http://www.gotocode.com/

11http://www.alistapart.com/articles/secureyourcode2/

12http://www.mozilla.org/js/spidermonkey/

13http://www.xssed.com/

14http://www.xssed.com/mirror/72143/

15http://www.xssed.com/mirror/72233/

16http://www.xssed.com/mirror/71974/